The Olympics may have come to a close, but those impressive displays of athletics got researchers at the University of Virginia questioning the muscular makeup of some of the world’s best athletes. To better understand which muscle groups powered elite sprinters, researchers conducted MRIs on 15 Division 1 sprinters and 15 average adults of the same age.

Olympic Athlete Study

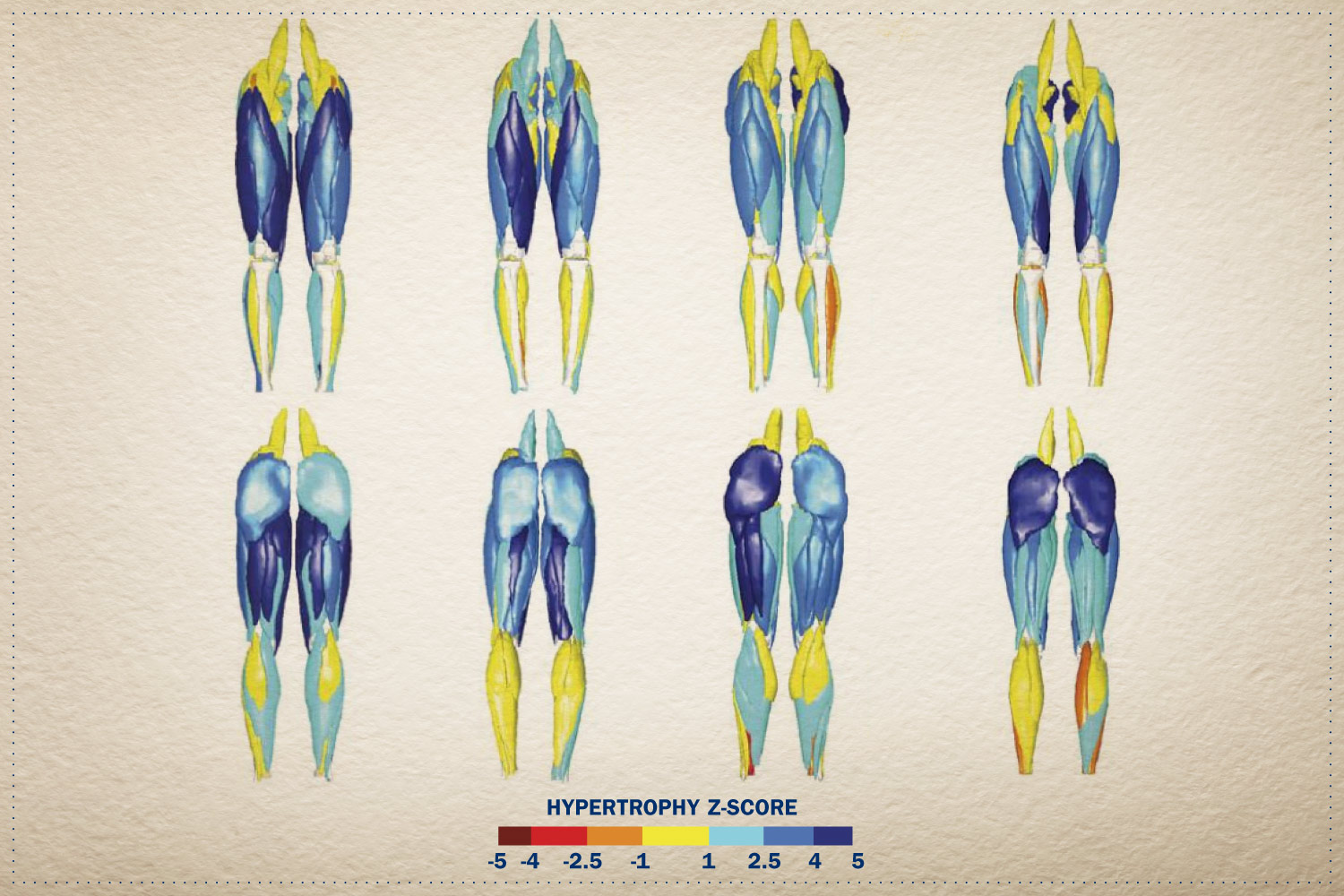

When the muscular images were compared, researchers uncovered that elite sprinters’ muscles were larger than those of non-sprinters. That’s not surprising at all, but where these muscles were bigger or smaller helped shed light on the muscle groups that power these elite athletes. According to researchers, the size difference in certain hip and knee muscles were very different between the two groups. Conversely, elite athletes expressed similar or even less developed ankle-crossing muscles than non-sprinters. Researchers say the results show that bigger is not always better, and that high performing sprinters have highly specialized patterns of muscle development throughout their lower bodies that are specifically advantageous for sprinting.

“One important outcome of our study is that simply adding mass to all leg muscles is likely not beneficial: only certain muscles should be strengthened to gain speed, while other muscles should likely remain smaller (to minimize mass),” said biomedical engineer and study author Silvia Blemker.

Here’s a look at the imaging taken during the study and Blemker’s words on what the picture shows.

We developed a highly visual method for illustrating the “patterns” of muscle hypertrophy for each athlete. In this figure, blue muscles are very large, yellow are “average” and red are small, as compared to a healthy non-athlete control database (while accounting for height and mass). We find this visualization to be highly effective for communicating our results with trainers, doctors, coaches and athletes.

I believe that genetics plays a role in speed, as it can many things that are important for running, including natural coordination, muscle fiber properties (including fiber type) and composition, musculoskeletal geometry, and likely other factors as well. However, our data indicates that muscle size/strength – a factor that can be developed through training – is also an important factor.